Rohan Hazarika, Senior Research Analyst at S&P Global Mobility discusses the recent ruling by the Bureau of Industry and Security.

The ruling by the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) is designed to address national security concerns related to the Information and Communications Technology and Services (ICTS) supply chain for connected vehicles. It specifically targets two critical systems: vehicle connectivity systems (VCS) and automated driving systems (ADS). VCS encompasses hardware and software that enable vehicles to communicate externally, while ADS includes software capable of performing the entire dynamic driving task.

The rule prohibits transactions involving VCS hardware and ADS software if they are designed, developed, manufactured or supplied by entities owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of the People's Republic of China (PRC) or the Russian Federation.

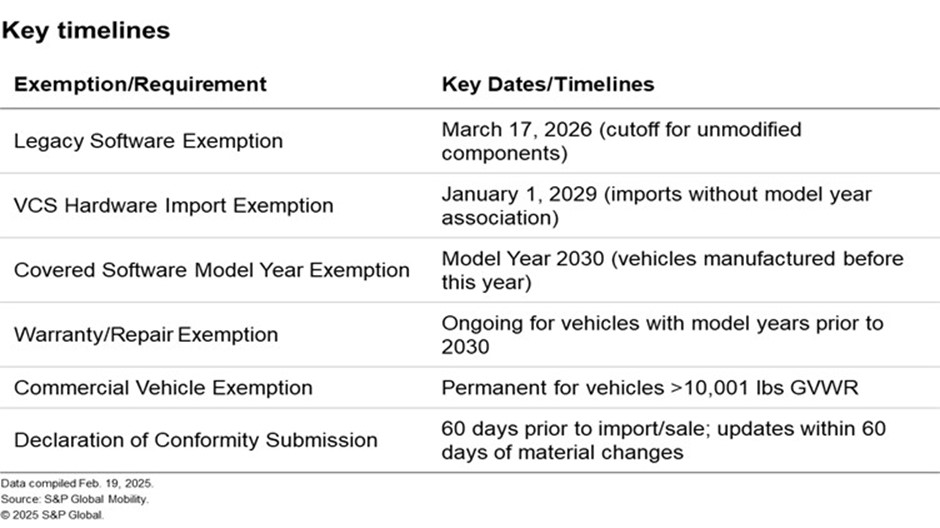

In terms of hardware transactions, the rule prohibits the importation of VCS hardware that is designed, developed, manufactured or supplied by entities with ties to the PRC or Russia. This includes components such as microcontrollers, microcomputers, cellular modems, Wi-Fi modules, Bluetooth modules and satellite communication systems. The prohibition applies to both stand-alone hardware and components integrated into completed connected vehicles. For example, if a US company imports a telematics control unit with a microcontroller manufactured in Russia, this would violate the rule. The rule also requires VCS hardware importers to submit declarations of conformity to BIS, certifying that their products do not involve prohibited transactions.

Similarly, in software transactions, the rule prohibits the importation and sale of completed connected vehicles that incorporate covered software designed, developed, manufactured or supplied by entities with ties to the PRC or Russia. Covered software includes application, middleware and system software that directly enables the function of VCS or ADS. This prohibition applies to both the importation of vehicles with such software and the sale of these vehicles within the US.

To ensure compliance, the ruling introduces several mechanisms. VCS hardware importers and connected vehicle manufacturers are required to submit declarations of conformity to BIS, certifying that their products do not involve prohibited transactions. BIS may also issue general authorizations for certain low-risk transactions and specific authorizations for transactions that can be shown to not pose undue or unacceptable risks.

Violations of the rule can result in significant penalties, including civil fines of up to $368,136 per violation and criminal fines of up to $1,000,000. BIS may also issue "is-informed" notices to flag prohibited transactions and require specific authorizations for continued operations. Entities found to be in violation of the rule may be subject to enforcement actions, including the seizure of prohibited components and software, and the imposition of injunctions to prevent further violations.

How does it impact ADS, ADAS and autonomous vehicle players?

The impact of this ruling is significant for both manufacturers and suppliers. They face increased due diligence and compliance costs, potential supply chain disruptions, and the need to source components and software from entities not subject to the jurisdiction or direction of the PRC or Russia.

The ruling prohibits the importation of VCS hardware, such as microcontrollers, cellular modems, Wi-Fi/Bluetooth modules and satellite communication systems, if sourced from restricted entities. These components are critical for enabling external communication in connected vehicles, including over-the-air updates and vehicle-to-everything systems. Autonomous vehicles rely heavily on these systems for real-time data exchange, and the prohibition could disrupt supply chains for connectivity modules. While legacy components designed before March 17, 2026, are exempt if unmodified by restricted entities, manufacturers must still conduct thorough due diligence to ensure compliance. Non-VCS hardware, such as sensors (cameras, radar, LiDAR), may also be impacted if their software drivers/firmware are considered covered software.

The ruling also targets software components that enable VCS or ADS functionality, including algorithms for sensor fusion, object detection and path planning. This impacts advanced driver assistance system features such as lane-keeping assist and adaptive cruise control, as well as the core software for autonomous driving. Proprietary software updates to open-source code are also prohibited if modified by restricted entities. Sensing technologies, such as LiDAR and radar, may face restrictions if their firmware or software drivers are developed by restricted entities. For example, a LiDAR sensor manufactured by a Chinese firm could be prohibited if its firmware is modified post-March 17, 2026, by a restricted entity.

For consumers, this could mean delays in the availability of new vehicle models and features, higher costs due to increased compliance expenses, and reduced choice in certain vehicle technologies. On the national security front, the ruling enhances protection against potential cyber threats and data exfiltration risks posed by foreign adversaries through the regulation of critical components and software in connected vehicles.

Global supply chains are shifting as companies pivot to suppliers in allied nations, such as Taiwan for semiconductors and South Korea for sensors. Local manufacturing of critical components in the US is also accelerating to reduce dependency on restricted regions.

ADAS suppliers like Bosch and Continental, with operations in China, may need to restructure supply chains to isolate restricted entities. For example, Bosch’s radar sensors or Continental’s telematics units could be prohibited if sourced from Chinese factories. Software startups like Zoox and other similar AV companies may need to shift to US-based or other cloud providers and open-source tools to avoid using services from restricted entities like Alibaba Cloud or Yandex.

Conclusion

Much of this geopolitical separation of supply chains was already underway for similar but distinct reasons. Mainland China is both big enough as a market to support local manufacturing from domestic suppliers and international companies alike. But local roads and driving behaviors are also distinct enough that local supply chains were already being built up to supply the local market. Still, this regulation punctuates the point strongly and concisely, and it means that any exporting from these plants to global programs becomes effectively prohibited (as long as the vehicle or component would be used within the US market).

The BIS ruling imposes restrictions on ADS/ADAS components and software tied to China or Russia, forcing autonomous vehicle players to reevaluate global supply chains. While exemptions provide limited relief, the rule’s emphasis on due diligence and supply chain transparency creates substantial compliance challenges. Companies must prioritize local sourcing, invest in secure software development, and engage in proactive risk mitigation to navigate the regulatory landscape while advancing autonomous vehicle innovation.

Manufacturers must now conduct extensive due diligence to trace the origin of components and software, ensuring no links to restricted entities. This includes third-tier suppliers, such as semiconductor foundries in China. Third-party assessments are allowed to verify compliance, but suppliers must maintain documentation for 10 years.

For more information, please click here.

Stay ahead of the latest trends by attending the industry’s largest coil winding and electrical engineering event.

Be part of CWIEME Berlin

Rohan Hazarika

Senior Research Analyst, S&P Global Mobility

Image courtesy of Cambridge Systematics